What to do about Ultraprocessed food: Finding Clarity through the Noise

In recent years, the term ultra-processed food has become more prominent in discussions surrounding nutrition and health. Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have sparked significant debate, particularly after the release of Ultra-Processed People by virologist and TV presenter Chris Van Tulleken. His claim that "ultra-processing, not the nutritional content" is the real health threat has made waves. Many of us are familiar with the general idea that highly processed foods aren’t ideal for a balanced diet. But what exactly is ultra-processed food , and what should we do about it? Is the answer as straightforward as it seems?

What is Food Processing?

Food processing can range from simple methods, like washing, cutting, and cooking, to more complex industrial processes, such as canning, pasteurisation, freezing, and the use of additives to improve flavour, texture, or longevity. The goal of food processing is to improve food safety, extend shelf life, enhance convenience, and sometimes modify the taste or nutritional content.

Understanding Ultra-processed Foods

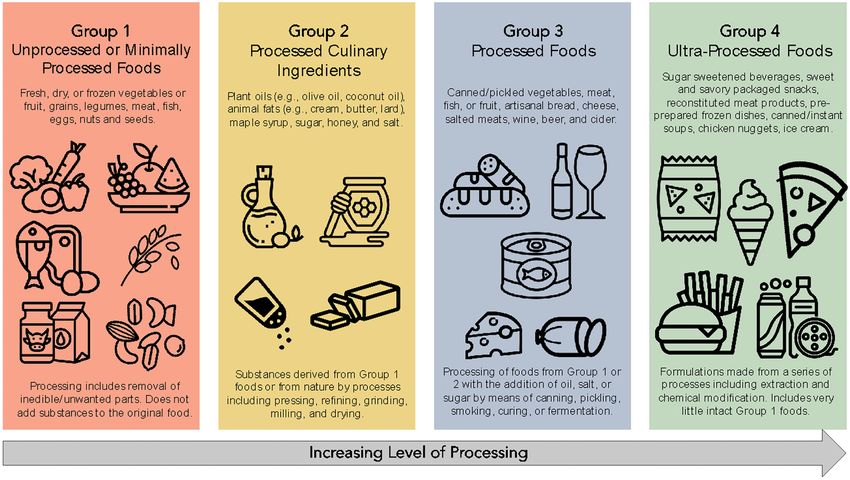

According to NOVA, a classification system which outlines the most widely recognised levels of food processing, there are four distinct processing categories.

UPFs are industrially manufactured foods containing ingredients rarely used at home—think preservatives, emulsifiers, flavour enhancers, and colours. Common examples include sugary drinks, snack foods, instant meals, and packaged desserts.

High consumption of these foods has been linked with diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity but Van Tulleken’s book takes this a step further. He claims it’s worse than smoking, which was the leading cause of death in Australia in 2018. But are UPFs truly the primary cause of early deaths, or is the danger exaggerated?

Separating Sensational Claims from Scientific Consensus

Van Tulleken’s assertion that UPFs are responsible for more deaths than smoking or other lifestyle factors is contentious. Most studies linking UPFs to health issues are observational. These studies can indicate correlations—like the connection between UPFs and obesity—but they can’t confirm that UPF alone is responsible for poor health outcomes.

For example, a recent study showed that high UPF consumption correlated with higher risk for accidental injuries, like car accidents, an outcome unlikely caused by the food itself but rather other unmeasured factors (known as confounding variables).

It's unclear whether various food processing methods and additives affect bodily processes that consequently, raise the risk of weight gain and chronic diseases, or if these risks are primarily due to the poor nutritional quality typical of ultra-processed foods. Many UPFs are energy-dense and low in essential nutrients, which complicates understanding their specific health impact.

Are All Ultra-Processed Foods Created Equal?

Even the NOVA food classification system, which categorises foods based on processing levels, faces criticism for grouping foods like wholemeal bread and sugary soft drinks under the same “ultra-processed” label. Bread, a staple that can contain nutrients such as wholegrains, cannot be equated nutritionally or health-wise to soft drinks. This further complicates the correlations established in the research surrounding UPF and health outcomes. Under this classification, canned beans, baby formula and life-saving fortification of flour in third-world countries, would also be deemed UPF.

This broad-brush approach has led to confusion, and consumers may feel overwhelmed by contradictory information. Moreover, fear-based messaging around UPFs can increase food anxiety, particularly among people already concerned about health or dealing with food insecurity. Some studies have differentiated the types of UPF that are more harmful than others, such as processed meats.

Known issues with Ultra-Processed Foods

Despite the debate, there are genuine concerns about UPFs. Most UPFs are designed to be hyper-palatable, which can encourage overconsumption.

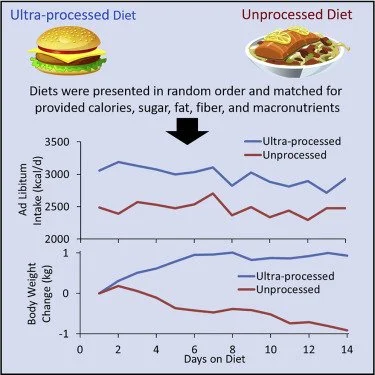

In a well-designed study, 20 adults were provided with minimally processed meals and ultra processed meals for 2 weeks each, which were matched for fibre, protein, fat and energy. They were instructed to eat as much or little as desired and when consuming predominantly UPF, the individuals unknowingly ate 500kcal more per day, leading to weight gain.

The link between ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption and obesity is not fully clear. It’s likely due to a mix of factors: the high-calorie, low-nutrient nature of UPFs, certain processing-related effects that are yet to be confirmed in human studies, and the fact that eating more UPFs often replaces healthier, unprocessed foods in the diet. It’s true that UPF’s such as chips, chocolate and soft drinks are often energy-dense and nutrient-poor, meaning they provide calories without significant vitamins, fibre, or essential nutrients.

Additionally, people who rely on UPFs may miss out on whole, unprocessed foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other nutrient-dense foods, which are crucial for long-term health. One study showed that, as the proportion of UPF’s in an individuals’ diet increased, all nutrient levels associated with non-communicable (i.e. non-transmissable) chronic disease were negatively impacted. This is undoubtedly concerning given the 2011-12 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey showed revealed 42% of Australians’ diets are comprised of UPF…

Some call for an overhaul of the dietary guidelines with a focus on the level of processing. Is this the answer we’re looking for?

The Australian Dietary Guidelines

The Australian Dietary Guidelines emphasise whole foods and limiting foods that are energy-dense and nutrient poor such as chips, chocolate and soft drinks, aka ‘Discretionary Items’.

In fact, similar data reporting on the proportion of UPF’s in Australians diets (42%) showed that discretionary items comprise 35% of intake. Some argue that explicitly including food processing levels could enhance consumer understanding and capacity to make better choices. However, many of the issues with UPFs are tied to broader social and policy influences, known as social determinants of health, rather than gaps in guidelines alone.

Social Determinants of Health

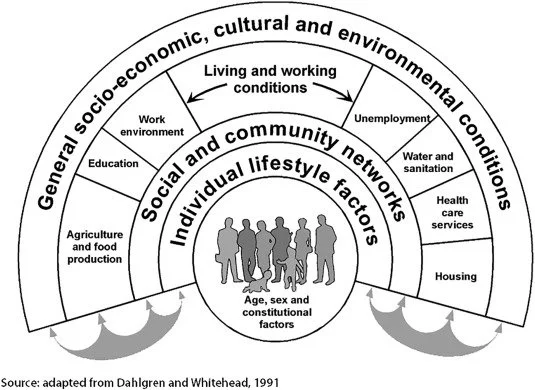

Health and illness consistently follow a social gradient worldwide, with individuals in lower socioeconomic positions experiencing a greater risk of poor health, irrespective of their country’s income level.

Advertising, accessibility, and economic factors make ultra-processed foods more appealing and accessible, especially to vulnerable populations. It’s no secret that McDonalds has greater reach than our national eating guidelines, is readily available and is more affordable. This is driven by multi-billion-dollar transnational corporations and a lack of government policies, such as marketing restrictions, food-labelling laws and regulations, to mitigate associated risks.

So, while refining healthy eating guidelines may (or may not) help, addressing the pervasive influence of UPF marketing and access to healthy food requires deeper social and policy-level changes.

So… Where does this leave us?

A Balanced Perspective: Reducing Harmful UPFs Without Overhauling Diets Entirely

While the concerns surrounding UPFs are valid, they’re best approached with nuance. Here are some practical tips to limit potentially harmful UPFs without overhauling your diet entirely:

Prioritise Whole Foods:

Incorporating more whole, minimally processed foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can enhance your diet without the need for extreme restrictions.

Limit High-Risk UPFs:

Reducing sugary drinks, processed meats, and heavily sweetened snacks can help mitigate health risks, while some ultra-processed foods (like fortified cereals or brown bread) might remain in your diet.

Cook at Home When Possible:

Preparing meals can improve dietary quality and give you control over ingredients. Not to mention, meal-prep can be a very cost-effective way to stay well-nourished compared to eating out.

Educate Yourself and Stay Sceptical:

While emerging research is useful, avoid sensationalist messaging that labels entire food categories as “good” or “bad.” Focus on balance and informed choices.

Support Policies for Healthier Food Environments:

Governments can help reduce harmful UPF consumption through clearer labelling, taxes on sugary drinks, and limits on unhealthy food marketing—steps that would help create a healthier food landscape from a systems level, without fostering unnecessary fear.

Moving Forward

The debate around ultra-processed foods isn’t going away anytime soon. While there is evidence linking high consumption of UPFs with health risks, sensationalist claims may oversimplify the issue. The truth is, we need more research to fully understand how UPFs impact our health, the issue is far more complex than just blaming the processing.

To make meaningful changes, the focus should be on a balanced diet prioritising whole foods, government policies promoting healthier options, and nuanced public health messaging. In the meantime, it’s all about balance.